By Josh Lehner

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

One big change during the pandemic has been that for the first time in recorded history, there were more deaths in Oregon than there were births. It’s been 18 months since we checked in on that here on the blog. We now have preliminary vital statistics for Oregon through June 2022 from OHA. (Data here: births and deaths)

In a word: yikes. In a 12 word summary of the implications: Without stronger migration trends, Oregon’s economic growth could be slower than anticipated.

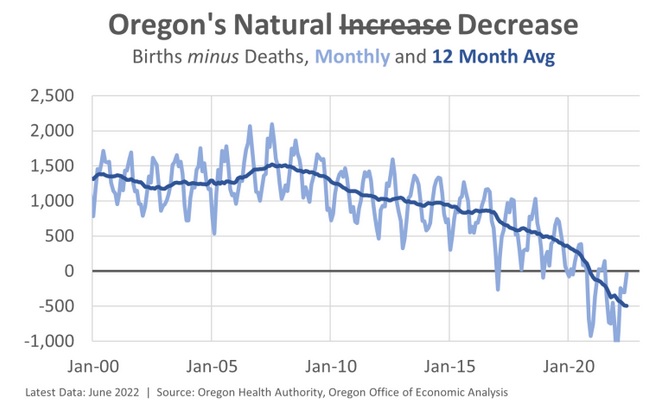

This first chart looks at what demographers typically call the population’s natural increase. It is the number of births minus the number of deaths. Given deaths now outstrip births, Oregon’s population is in a natural decline. That means if we were to wall off Oregon and nobody could come or go, our population would start shrinking tomorrow. Note that there is a distinct seasonal pattern here driven by the fact that births tend to be higher in the summer and lower in the winter, whereas deaths tend to be higher in the winter and lower in the summer. The 12 month average continues to plumb new lows.

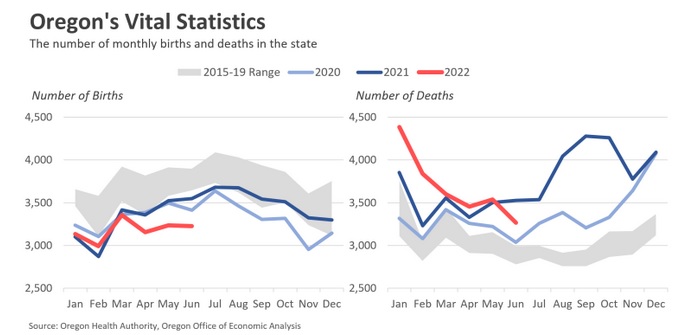

Of course any time we are talking about a number made up of multiple underlying numbers, it is always useful to decompose the changes and explore what is driving the topline. When we separate out the changes seen in the number of Oregon deaths and births we find one silver lining and one ongoing concern.

Let’s start first with deaths. Even as Oregon’s overall public health has been considerably better than most states throughout the pandemic, we are not immune. Comparing the actual number of deaths in the state to our office’s pre-pandemic forecast shows Oregon has suffered about 10,400 more deaths than expected (of all causes) so far. This is tragic for all of us who lost friends, family, and neighbors. The silver lining is the number of deaths has fallen in recent months and is now back within the range of our pre-pandemic expectations. Note that with a growing, and aging population, the number of deaths in Oregon is expected to increase in the years ahead for demographic reasons alone. As such we are unlikely to return to the number of deaths seen a handful of years ago.

Now let’s turn to the latest data on births. Nationally there has been some chatter about the uptick in births in late 2021 and how it was better than the 2020 pandemic lows. That uptick has proved short-lived. The baby bust continues. I have monthly birth data back to 1998, so 25 years of data. The most recent few months — April, May, June — are each the lowest such months in the past 25 years. So far, 2022 is on pace for the fewest total births in the state since the mid- to late-1980s. Oregon’s population back then was about 2.7 million residents, or nearly 40% smaller than today’s nearly 4.3 million residents.

Finally, a few thoughts on the outlook, and what it all means.

The forecast calls for Oregon’s natural decrease in the population to continue, but not accelerate further. The primary reason is the number of total births is expected to increase some in the years ahead. With a growing population, a steady, or stable birthrate means the total number of births will increase. The risks here are balanced. There could be a small, but meaningful increase in the birthrate coming off the pandemic lows (even if we haven’t seen it yet in the data, it does seem plausible and within the realm of possibilities). For example, the number of first-time mothers in 2021 has actually pretty typical of what we saw pre-pandemic, although that has fallen off again in the 2022 data. Just something to keep an eye on.

In terms of the significance, as this post led off with, Oregon is increasingly reliant upon migration to grow our economy and labor force. Without net in-migration, our workforce will shrink in the decades ahead. Our forecast calls for population growth to pick up this year and next following the pandemic slowdown. We will get the 2022 Portland State population estimates in November, and Census Bureau estimates in December.

Another impact here is on child-related activities and services, including education and even things like the type of housing people want or need. In terms of education our office’s forecast for the K-12 population (total number of Oregon children 5-17 years old) was already for a 6% decline from 2020 to 2030 even before the latest data. And of course this will impact the traditional college-age cohort in the 2030s. One note on childcare facilities themselves, we know Oregon has a shortage today, so even with the decline in births it does not mean we will suddenly be oversupplied, it just means demand could be coming down closer to existing supply.

One more thing, we know that there is considerable variation around the state when it comes to demographics. Many rural areas have already seen deaths outnumber births for a decade or two. But not all rural areas, as those in the Gorge and Northeastern Oregon have seen better trends. But these underlying demographics are something our office was focusing on quite a bit pre-pandemic. Here we talked about the labor force outlook across counties, and if not labor, we need to better use our different types of capital to grow the regional economy. More recently we reported on Oregon’s Latent Labor Force which can help boost the local economy when the labor market is tight.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.