By Josh Lehner

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

Labor market dynamics are shifting. Job growth will be more balanced across industries. Job gains will moderate in a full employment economy, slowing aggregate wages along the way, which should help lessen some inflationary pressures as well. However, a structural labor shortage remains given the strength in the underlying economy and firms struggling to fill positions due to pandemic-related changes.

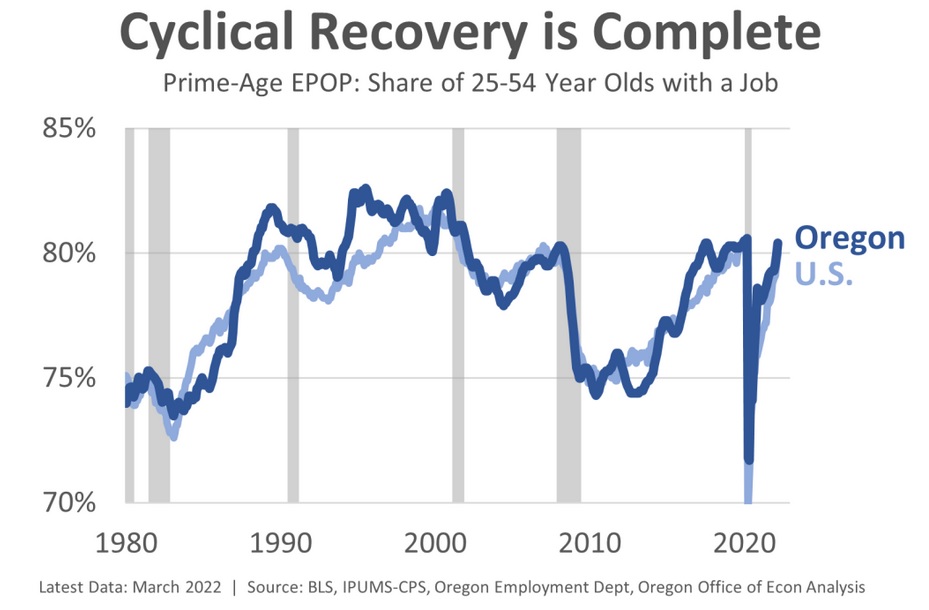

Let’s start with the good news. Today, we are no longer talking about cyclical labor supply issues related to the recession, the pandemic, lack of in-person schooling, enhanced unemployment insurance benefits, or anything like that. Those are all in the rearview mirror. Labor supply has rebounded considerably in the past year, over which time Oregon added more than 100,000 jobs. The U.S. has added more than 6 million jobs over the same time period. Folks are not just sitting on the sidelines waiting to return; they have already returned. The share of the prime working-age population that has a job today is effectively has high as we have experienced this millennium.

For firms it may have felt like pulling teeth to reach this point. We know labor demand increased quickly given strong household incomes and consumer spending. Workers have returned to take advantage of the more-plentiful and better-paying opportunities, although this return was slower than the increase in job openings. But we have now reached the point where employment levels today are essentially back to where they were pre-pandemic. And encouragingly, the labor force participation rate for the prime working-age group has likewise rebounded and is now just a hair below the pre-pandemic peak nationally.

So if these cyclical issues are largely gone, why does a labor shortage remain? This is where the bad news comes in. Besides the strong underlying economy, which is a big part of it, I see a combination of three shifts during the pandemic, and three big structural changes.

In terms of the three pandemic shifts, the first is that self-employment is up. About 20,000 more Oregonians are self-employed today than in the years leading up to the pandemic. Second, there are around 16,000 fewer multiple jobholders today. Both of these trends mean the number of Oregonians with a job is higher than the underlying payroll job counts indicate, which is something we see comparing the household and establishment surveys.

The third pandemic shift has been the increase in the number of workers quitting their jobs. Now, they are not quitting and dropping out of the labor force. Rather they are quitting one job to take another one. Quits in Oregon are up about 5,000 per month. Combined, all three of these factors leave businesses with more job vacancies today even if their desired staffing levels are the same as pre-pandemic.

In terms of the structural factors, the first is the outright decline in foreign-born workers as discussed before. A silver lining here is that in the past handful of months the U.S. numbers have really rebounded. That has yet to show up in the Oregon data, but should in the months ahead. There is a risk here that some of these observed changes — both up and down — in the data are noise from a small sample of a hard-to-reach population. Even so, we know international immigration has slowed considerably even if such outright declines end up being noise.

Second, we cannot ignore the tragic loss of life from the pandemic itself. Oregon has suffered 9,500 more deaths in the past two years than our office was expecting pre-pandemic. This “excess death” type calculation is likely to rise further, and is larger than the 7,500 official COVID-19 deaths to date. Adjusting these deaths by age and labor force participation rates finds that Oregon lost an estimated 2,500 workers during the pandemic. Such a figure is equal to about one month’s worth of job gains in a full employment economy, and unfortunately is a structural factor.

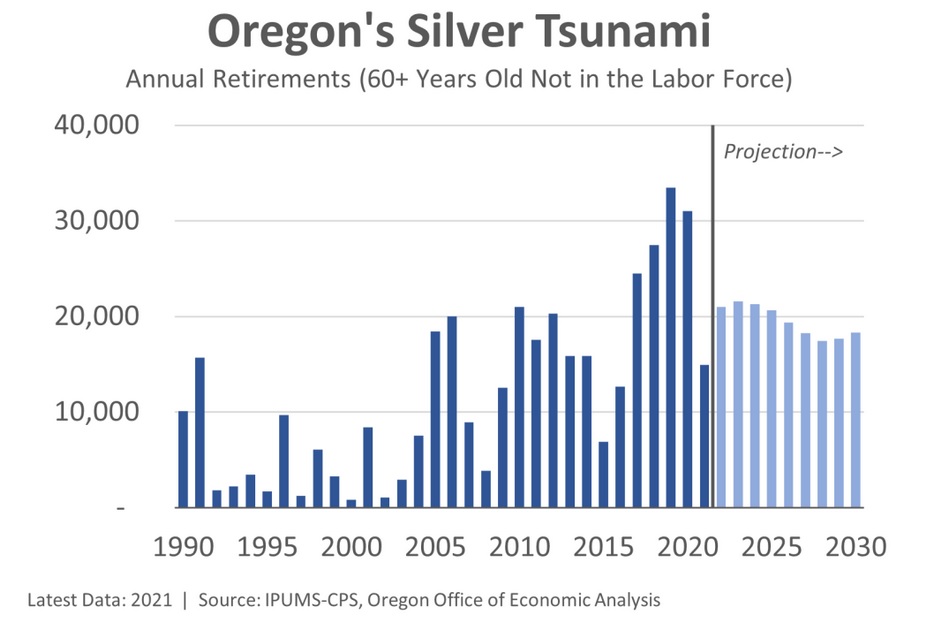

Finally, the biggest reason for a tight labor market today and in the years ahead are demographics. The big Baby Boomer generation is retiring, something our office has been highlighting repeatedly over the years. The new, younger entrants into the labor market are a steady, but not increasing flow due to the declining birth rate in recent decades and slower migration during the pandemic. The bottom line is the labor market is and will continue to be structurally tight for these demographic reasons.

Overall the good news is the cyclical issues we have been worried about are effectively gone. The bad news is we still have an “unsustainably hot” labor market in the words of Federal Reserve Chair Powell. Most of this is now due to structural factors like excess demand, and mediocre demographics. Tighter monetary policy can, and will help with the former, while the latter will only change with broader societal shifts or, say, increased immigration both international and domestic in the case of Oregon.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.