By Josh Lehner,

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

Large metro areas led the recovery coming out of the Great Recession. Portland’s growth last decade was transformational. Among the 100 largest metros in the country, Portland ranked in the Top 10 for high-wage job growth, median household income gains, and increases in educational attainment. The region’s urban core also transformed physically with numerous apartments, hotels, and offices being built, helping create an attractive place to live, work, and play.

This cycle is different. During a pandemic, urban amenities like walkable neighborhoods and clusters of knowledge workers turn into dis-amenities. Portland is now the worst performing regional economy in the state. The primary reason is the lack of in-person activities that cities normally thrive one. With more individuals working from home and business travel just now starting to pick up, urban cores to date are not quite themselves. There just aren’t as many individuals going out to eat, window shopping, or staying in hotels.

However, incomes and consumer spending remain strong. It’s just more of that spending is occurring in suburban and rural areas as workers eat and shop closer to home. As seen above, the City of Portland is trailing the rest of the region and state in many in-person activities. Specifically, the number of people going out to eat is only halfway recovered, while it is fully recovered elsewhere in the state. Video lottery sales, a measure of consumer spending in bars and restaurants, are fully recovered in downtown Portland, but they are even stronger in the suburbs and rest of the state. Similarly airline passenger travel is effectively recovered in Eugene, Medford, and Redmond, while not so at PDX. As a result of fewer overall visits and trips into the City of Portland, leisure and hospitality employment remains depressed. In 2019 leisure and hospitality employment in Multnomah County accounted for 11% of all jobs, however today the industry accounts for nearly 45% of the employment shortfall relative to pre-pandemic peaks.

However, these general dynamics are not unique to Portland. Across the country, large urban areas with populations of at least one million residents are trailing their smaller urban and rural counterparts. In fact, economic data show that the Portland region is right in line with the experiences of these other big metros. As of October, employment in the Portland metro is down 4.2% from pre-pandemic levels, effectively identical to the 4.3% decline seen in the median large metro. Now, earlier in the pandemic, Portland did trail the typical large metro by a couple percentage points – likely impacted by the more stringent public health policies that helped slow the spread of the virus – but that gap closed in recent months.

While Portland overall is in the middle of the pack this can be thought of as both good and bad news. On the good news front two things stand out. First, despite the pessimistic narrative or portrayal of Portland – a place where protests turn violent, a place that has been burning for decades according to the former President of the United States, a place overrun with homelessness, and the like – economically the region is average. Societal ills are not to be ignored and do need to be addressed. For example, we know homelessness is primarily about the inability to afford housing, largely the result of not building enough housing in recent decades. However there is also a distinction between some of these societal challenges, public perception, and underlying economic performance. In terms of the economy, there is nothing fundamentally wrong with Portland.

Second, Oregon’s economy tends to be more volatile than the nation overall. We usually experience more severe recessions, and faster economic expansions. So far this cycle, Portland, and Oregon are experiencing an average-sized recession. The local economy is not starting from the bottom of the pack, like usual.

On the bad news front, while Portland may be pretty typical, the region does trail every one of its peer metro areas. As identified by the Portland Business Alliance, based on research from ECONorthwest, these peer metro areas are: Austin, Indianapolis, Nashville, Salt Lake and Seattle. Admittedly, these are very tough comparisons. Austin and Salt Lake are the two fastest growing large metros in the entire country. Portland is gaining noticeable ground on Indianapolis and a little on Nashville, making up some of the earlier differences. Portland and Seattle’s labor markets are moving in tandem, likely due to similar pandemic trajectories and health policies, but Seattle employment is running about one percentage point stronger. While these peers are among the fastest growing regions in the entire country, and make for challenging comparisons, Portland was certainly included in the same group last cycle.

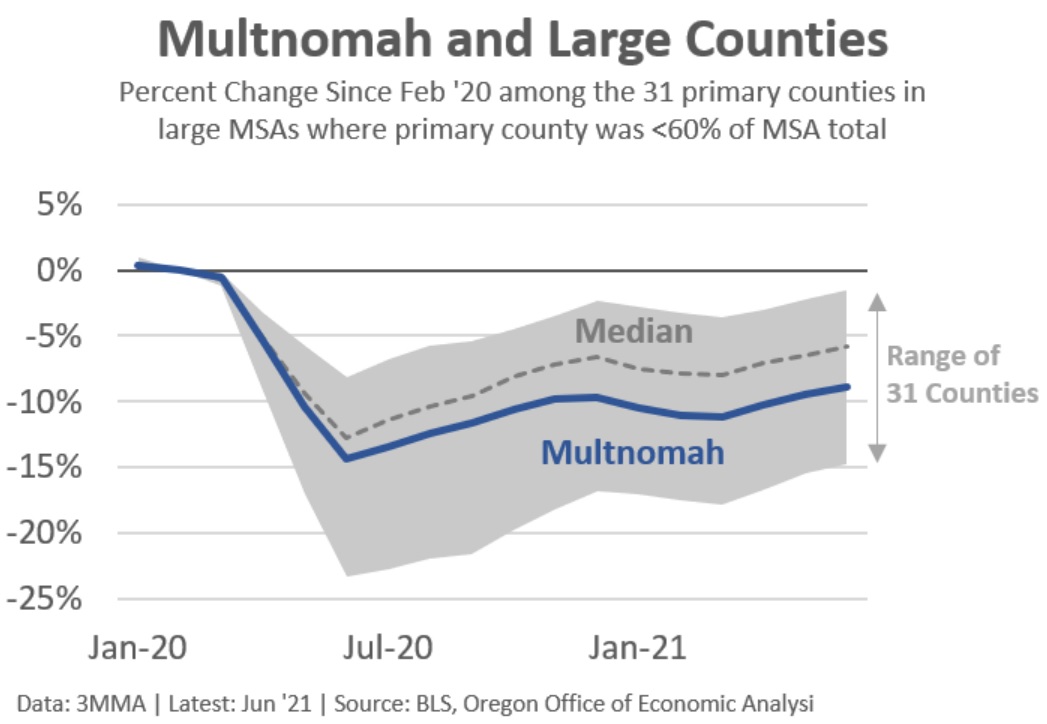

While at the regional level, Portland is following trends seen throughout the country, what about the City of Portland and downtown in particular? Afterall, it is the urban core where the protests and violence occurred, where our unhoused neighbors are more visible, and where workers are making fewer commuting trips. The challenge here is data availability. A lot of economic data is published at the state, metro, and county level. In Oregon, counties work well for analysis but this is not the case everywhere. For example, the entire metros of both Phoenix and San Diego are contained within a single county. There is no ability to look at the city versus suburbs in the standard economic data. Thankfully 31 of the largest metros in the country have somewhat useful county level granularity. Even so, the best employment data at the county level lags considerably. Detailed county level data is only available through June 2021. Data through September 2021 will be released in February 2022.

Even so, as of June 2021, Multnomah County employment since the start of the pandemic does trail the median large urban county by 3 percentage points. At the metro level, Portland trailed the median by 1-2 percentage points back in June. This is one indication that the city versus suburbs divergence may be a bit more pronounced in Portland than in some other metro areas, but not necessarily entirely so. To the extent it is, it is more a matter of degree, not kind based on the imperfect data available. This is an important metric that our office will continue to monitor closely in the quarters ahead.

Employment is typically a good, real-time gauge of economic activity and growth. However, due to federal aid during the pandemic, this usual connection broke down. One of the explicit goals of federal policy was to ensure that Americans did not have to work during a pandemic just to put food on the able, if they did not want to. The goal was to slow the spread of the virus, with as few financial repercussions for businesses and households as possible. Between enhanced unemployment insurance benefits, recovery rebates, student loan deferrals, rent assistance, and the like, federal policy more than did its job.

In fact, as seen in the scatterplot below, overall income growth across metro areas last year was actually pretty consistent, regardless of local economic conditions. The blue dots are primarily in the +5-10% range for total income growth last year. However if one focuses just on the impact of job losses on wages and salaries, the relationship is quite clear. The gray dots show that larger job losses result in fewer wages earned. The difference between the gray and blue dots, again, is the substantial federal aid supporting household incomes everywhere, and more than enough to offset the variation in local job losses.

Specifically for Portland, the region lost 6.3 percent of its jobs on an annual average basis, which is noticeably larger than the median metro’s losses of 4.9 percent. Even so, Portland’s total income grew 7.0 percent last year despite the severe recession. Portland’s total income growth was just a hair stronger than the median gain of 6.9 percent across all metro areas.

A similar pattern is seen if we focus just on Multnomah County relative to both all counties in the U.S. and the other primary counties in large metro areas. Multnomah’s employment last year fell 7.6 percent which is noticeably larger than the typical U.S. county at 4.3 percent. However total incomes in Multnomah increased 7.9 percent which outpaced the typical U.S. county’s 7.6 percent gain. Specifically comparing Multnomah to the primary counties of the region’s peer metros, Multnomah’s income growth stands out last year. Income growth in Marion County, Indiana (Indianapolis MSA), Davidson, Tennessee (Nashville MSA), and King County, Washington (Seattle MSA) were all slower than Multnomah. Reasonable county granularity is not available for either the Austin or Salt Lake MSAs.

While local economic conditions may have mattered less in the past year and a half than at any point in recent memory, the recovery is now at a crucial junction. The federal aid is gone. Local growth once again is in the driver’s seat.

Near-term growth will largely be about consumer spending on services picking up as we return more to our daily lives. Service industries are labor-intensive, which will drive strong near-term employment growth in the quarters ahead. A piece of that of will be white collar workers return to the office a bit more, going on more business trips and the like, which supports urban cores and jobs centers across the country.

Long-term economic growth is about the number of workers a regional economy has and how productive each worker is. Portland, and Oregon more broadly, have benefitted substantially in recent decades from an influx of young, skilled households moving here, and strong business investment. The question today, given the pessimism built into the conventional wisdom, is whether Portland’s longer-term growth prospects have been diminished. Is the region now a less desirable place to live, or run a business? Only time will tell. However, there are a few green shoots seen in the data.

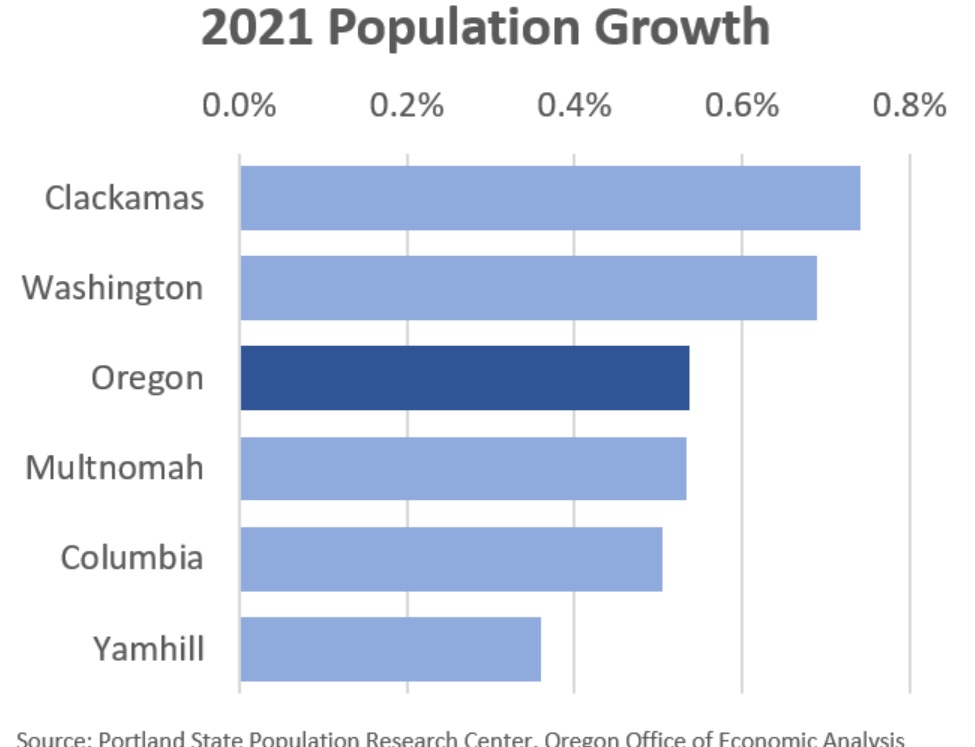

First, Portland State University’s Population Research Center recently released the preliminary 2021 county and city population estimates for Oregon. Typically during recessions, population growth slows as job opportunities are fewer and harder to come by. Population growth slowed in 2020, due to the pandemic and recession, and these slow gains continued into 2021. Some of the underlying details are not yet available, neither are revisions to population estimates last decade following the delayed release of the 2020 Decennial Census data.

However it is important to keep in mind that population growth it is still positive. More people moved into Oregon, the Portland region, and Multnomah County specifically than moved out. Expectations are that this net in-migration will strengthen in the years ahead as it typically does, bringing with it an influx of mostly younger, mostly skilled workers. This boosts longer-term economic growth prospects overall as local firms can hire and expand at a faster rate due to the larger workforce.

Second, Portland’s reputation as a good place for business investment took a hit a year ago. For example, in last year’s Emerging Trends in Real Estate annual report from the Urban Land Institute, the Portland market dropped from its normally high-ranking spot to 66th best nationwide. In this year’s report, Portland rebounded to 49th best, which was the 10th largest increase in the rankings, but still lower than where the region ranked pre-pandemic. The biggest increases for Portland among the subcategories were in the local economy, and local public and private investments, while the region saw a relative decline in the investor demand subcategory.

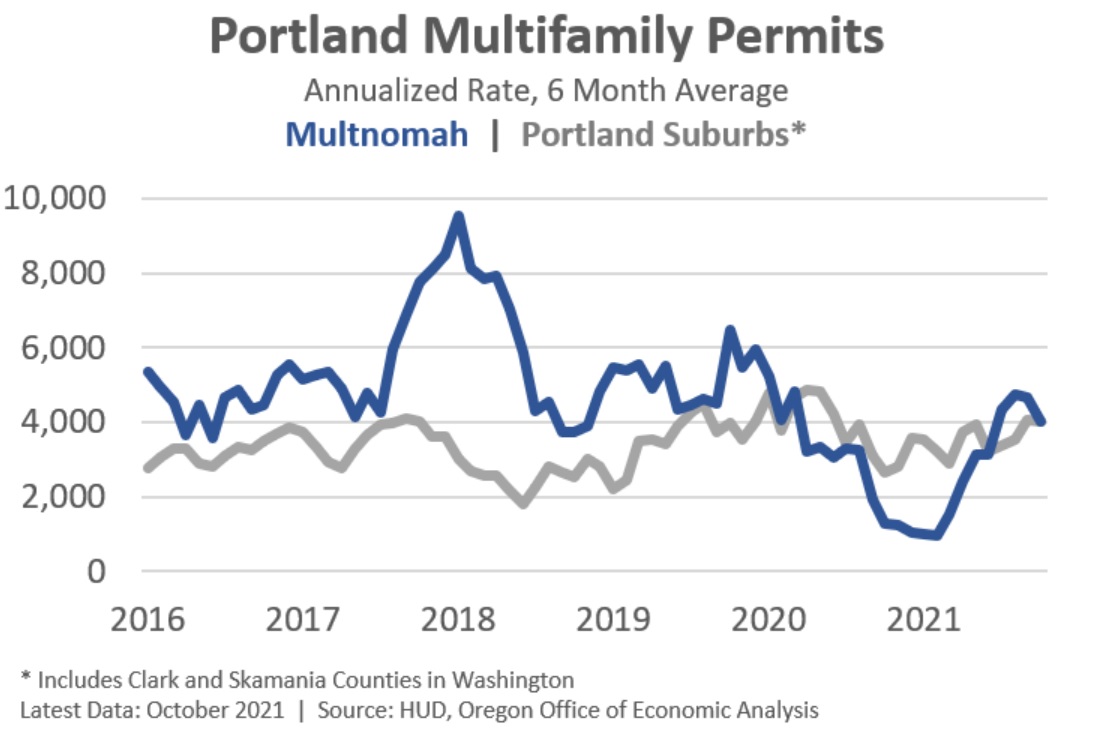

While the ULI report is a survey based on market perceptions and investment opportunities, there is also a bright spot in the actual new construction permitting data. Initially, multifamily (apartment) permits dropped considerably at the beginning of the pandemic. Projects were put on hold, or worse, even canceled given the uncertain economic outlook and public health situation facing large cities nationwide. Encouragingly, permits for new apartment buildings in Multnomah County have been picking up throughout 2021. Today, the pace of new permits issued is nearly back to where it typically was pre-pandemic. It is not yet a full recovery, but at this point it looks to be more than just an encouraging trend.

The rebound in permitting activity, which will turn into economic activity and investment in the months ahead, is overall great news. One concern, however, is that the recent uptick may reflect delayed projects once again moving forward. While still good news, this could mean the permit activity overstates the actual increase in underlying demand and investment. Our office will continue to closely track new construction activity in the months ahead.

On the other hand, the need for more housing continues. Following a sizable building cycle in the urban core last decade, the apartment vacancy rate rose as more supply came on the market just as the pandemic hit. This was one reason why Portland’s investment opportunities and perception declined, because segments of the market were beginning to be overbuilt.

Now, today the vacancy rate is declining and rents are rising. There are legitimate underlying market fundamentals supporting more construction. This points toward an ongoing economic recovery and increase in investments. Given housing affordability is a key concern our office has in terms of the ability to attract and retain workers, the regional economy needs more new construction.

Bottom Line: Ultimately people vote with their feet and their wallet. Expectations are that Portland, and Oregon more broadly will remain an attractive place to live and work. Most households move for quality of life, job opportunities, and/or housing reasons. As such, the regional economy is likely to experience above-average growth in the years ahead. The outlook is bright. Already the region has caught up economically to other large metro areas despite local social challenges and public perception. However, the key question is whether or not Portland will reclaim its perch among the highest fliers around the country, which remains to be seen.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.