By Josh Lehner,

Office of Economic Analysis

Coming out of the Great Recession it was the nation’s largest urban areas that turned around first. Being home to the most diversified economies also meant less exposure to housing and government, the two biggest drags last cycle. In part due to the more-plentiful job opportunities, and in part due to increased preferences for urban living, strong population gains to the larger metropolitan areas reinforced these economic dynamics, driving a stronger recovery in urban areas than in many smaller metros and rural communities.

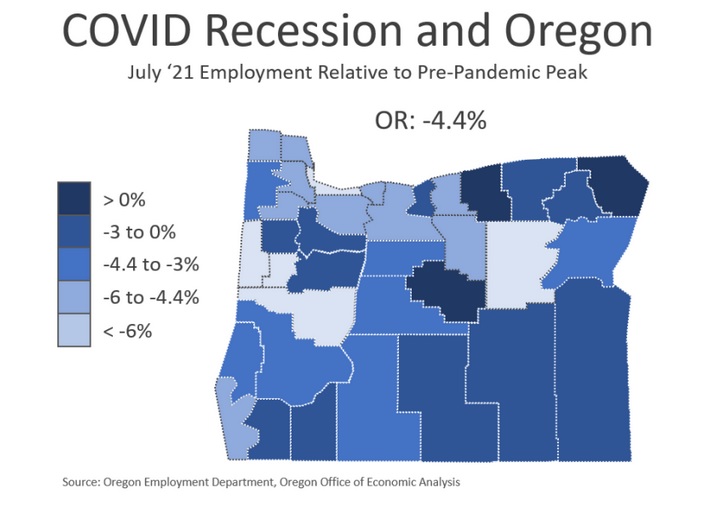

This cycle is different. Oregon’s large urban areas are lagging the rest of the state. This is due to a number of factors including less business travel, more working from home, and all those great urban amenities being transformed into disamenities when they cannot be used or enjoyed during a pandemic. All of these are key factors impacting urban areas nationwide before one gets into any discussion of the impacts from local protests and clashes of violence. Our office’s view is that those impacts are negative, likely contributing to a larger local decline versus other coastal, and/or northern metro areas (the south instituted fewer public health restrictions). While we need better, and more granular data to do a proper comparison, the clashes of violence are likely to be more of a secondary impact, relative to the more primary impacts of working from home and lack of business travel.

Over the medium- and long-run, the Portland economy is expected to regain its position near the top of the pack. Economic growth is fundamentally about how many workers a region has and how productive each worker is. Population growth will strengthen during the recovery, bringing with it an influx of new workers and new firms that will outpace much of the state and nation. Human capital accumulation and agglomeration effects will boost urban economies to a greater degree. Plus urban areas tend to have larger pools of financial and physical capital to help drive productivity gains in the years ahead. The wildcard in terms of downtown Portland and job centers more broadly remains working from home. Ultimately where that lands, be it a couple days a week versus fully remote, will go a long way to determining the impact on commercial real estate.

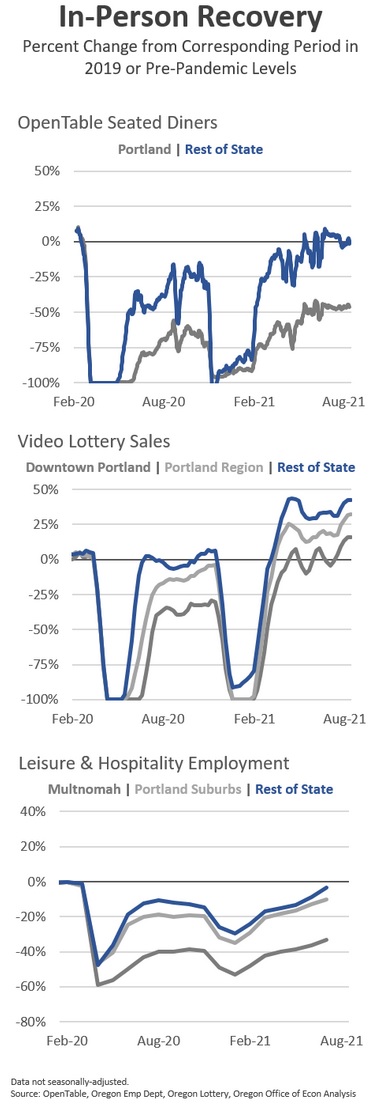

However, with the pandemic still raging, the Portland regional economy is still suffering more than the rest of the state. In particular it is the in-person activities that cities usually thrive on that are seeing slower gains than elsewhere around the state. It is somewhat of an open question just how much of these differing trends can be chalked up strictly to the pandemic itself, versus how consumers behave differently across the state in response to the pandemic. Nonetheless, Portland’s in-person recovery is lagging the rest of the state.

Click here for the same charts but in horizontal layout, which doesn’t work well in blog format but does for other formats like slides and documents.

In the Portland region, the number of seated diners at restaurants is only halfway back to where it was before the pandemic, compared with a full recovery in other parts of the state, at least among restaurants using the OpenTable reservation software. Note that in recent weeks, the weakening in indoor dining is not seen in the Portland region but elsewhere in the state where cases and hospitalizations are much higher during the delta wave, and vaccination rates are likewise lower.

One bright spot for tracking the recovery in downtown Portland is that video lottery sales in the urban core have fully recovered, and set records this summer. While an imperfect measure, it does indicate that foot traffic and consumer spending are returning. However, in keeping with the broader patterns in the economy, these gains in video lottery sales are larger in the Portland suburbs, and strongest elsewhere across the state.

Lastly, the relative economic performance is seen in the employment data as well. Leisure and hospitality employment in Multnomah County remains down three times as much as in the Portland suburban counties, and ten times as much as in the rest of the state, with data available through July.

Two major contributing factors remain the lack of business travel during the pandemic, and the increased number of people working from home. Both issues work to lower the number of consumers in the urban core, while simultaneously boosting their home markets, be they out of state or in the suburbs. In some hot off the press new NBER research by Althoff et al (2021), they write when it comes to working from home that “[t]he larger a neighborhood’s initial share of high-skill service workers among its residents, the larger its decline in visits to local consumer service establishments and the sharper the drop in residents’ spending on consumer services.” The authors go on to conclude “[i]f the recent pandemic is any guide, high-skill service workers will benefit from increased spatial flexibility and make use of it, while low-skill service workers will suffer from their dependence on local demand in a more footloose world.” This pattern is borne out nationwide, and here in Oregon as shown above.

Again, over the entire cycle our office is bullish on the future of large, urban economies. And to the extent there are some structural changes nationally, Portland and Oregon more broadly are likely to benefit overall. Pre-pandemic, every region of the state was average or above average in working from home. However, the pandemic is still raging, and many in-person activities, while growing again, are still significantly below pre-COVID levels.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.