By Josh Lehner

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

This week we got the May 2020 employment report for Oregon. Like the U.S., it was a happy surprise in that jobs grew and unemployment declined. Today I just wanted to highlight the data, update our charts, and introduce a new piece of research. Next week I will follow-up with more thoughts on how our office is working through the report’s implications and what it means.

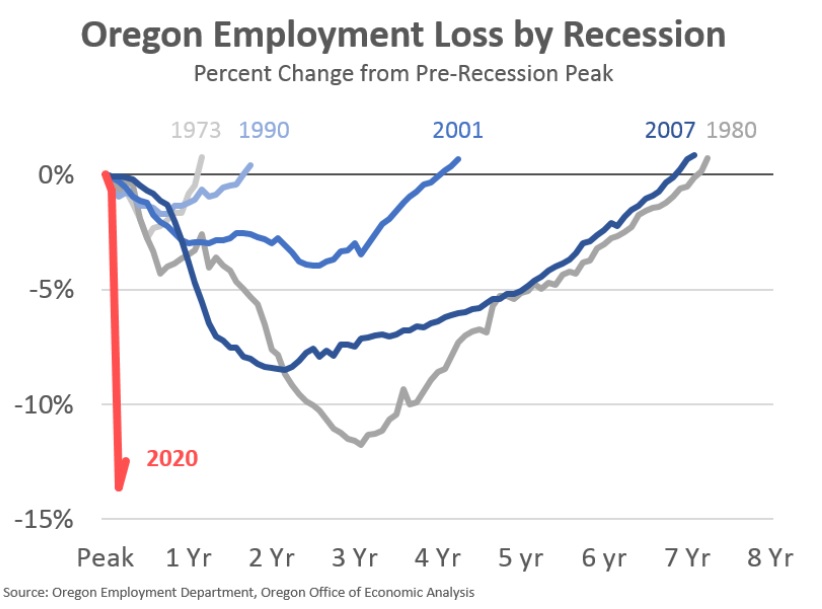

First, the good news is that in May, Oregon added back about 1 out of every 12 jobs lost during earlier in the recession. The state remains in the deepest, or most severe recession on record, with employment data back to 1939. However those losses are no longer mounting based on the latest data. This truly is good economic news!

Now, this rebound in employment was a bit of a surprise and I’m of many minds right now trying to parse out what it means. On one hand this shouldn’t really be a surprise. High frequency economic data all point toward early May as being the worst of the recession, with things getting better since. At some point, economic growth does translate into net employment gains. The standard monthly data are all starting to bear this out with jobs up, unemployment down, industrial production and consumer spending rising, and the like.

Now, on the other hand, what was surprising was the good jobs report with the backdrop of initial claims for unemployment insurance continuing to come in higher than anything seen in past recessions. This is true even in the most recent few weeks.

The question is what happened? How much of this potential disconnect is about workers seeing hours reduced enough to claim UI but not being fully laid off? How much is due to the fiscal impact of the CARES Act? Are we waiting for another shoe to drop as the permanent damage mounts even as topline data improves? Or is the economy truly better, and proved much more resilient than expected? Were forecasters simply too pessimistic? I’ll have more thoughts on some of this next week regarding business and sector risks, and potential permanent damage.

But before then I wanted to introduce some new research I find very helpful to think through some of the current labor market data.

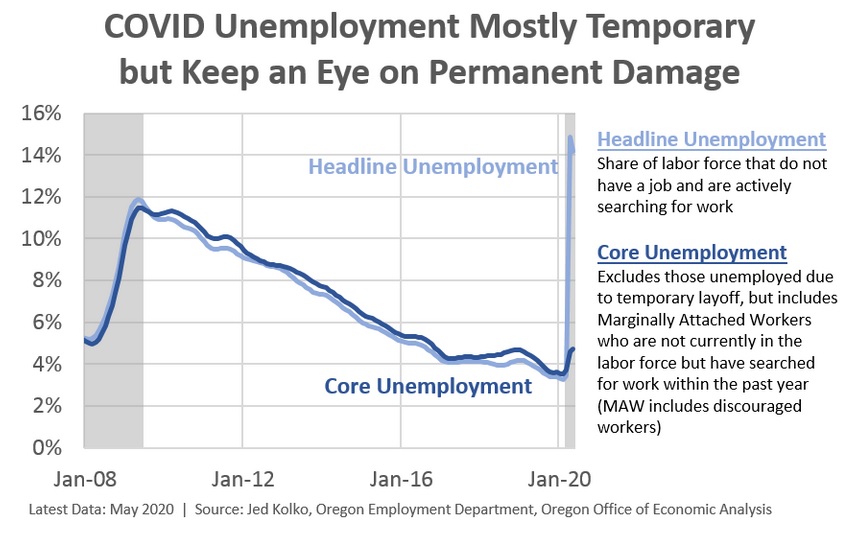

Indeed’s chief economist Jed Kolko pioneered a measure on Twitter the other week and recently wrote up his findings in The New York Times. The idea behind Jed’s work is to gauge the difference between permanent and temporary damage in the economy. We know most of the layoffs in recent months are/were expected to be temporary. In Oregon, when firms notify the state of layoffs, 86% of those layoffs are expected to be temporary. And if you look at the Oregon household survey data, about 75% of currently unemployed Oregonians are classified as on temporary layoff (the others are permanently laid off, or entrants into the labor market, or those who quit their jobs, etc).

As these workers are recalled to their jobs, we will see improvements in the topline data, which is great news overall. But it may also mask some darker, or more permanent changes seen in the economy. Jed’s calling his new measure the core unemployment rate and the calculation does two things. First it excludes all those unemployed on temporary layoff. Second he adds back in the marginally attached workers, or those who are not currently looking for a job but have looked for one in the past year.

The first part gets to the permanent layoff component and also those who are looking but can’t find work as firms aren’t hiring. The second part gets at any short-term participation rate issues where people stopped looking for work during the pandemic but otherwise may want a job. Keep in mind that discouraged workers are a subset of marginally attached workers, which is a bit broader by definition.

The chart above is an Oregon version of Jed’s core unemployment measure. Three things to note. First, a huge thank you to Tracy Morrissette over at the Employment Department for his great work digging into the details of the data that allowed me to recreate this. Second, the vast majority of the increase in the unemployment rate is expected to be temporary. Third, even so, the amount of permanent damage has increased, albeit relatively modestly so far. The core unemployment rate in Oregon has increased by just more than 1 percentage point, while the headline unemployment rate has increased by about 11 percentage points.

The key issue to watch moving forward will be how much or how little of the expected temporary economic pain turns permanent. Even under optimistic assumptions, it will take time to get back to full employment. There will be increases in firm closures and the number of long-term unemployed as a result of the recession. However, should the amount of permanent damage that accumulates be relatively small, then the recovery will be stronger and the economy will return to full health sooner. We will continue to monitor these changes in the months ahead.

Stay tuned next week for a few more thoughts on the data, the risks for businesses and sectors, and comparisons with our forecast.

Note: Economist Jason Furman has a somewhat similar concept, a measure he calls the full recall unemployment rate. It’s a bit more complicated of a calculation and is really designed to adjust for both the temporary layoffs, but also any real labor force participation rate issues. Here in Oregon our labor force participation rate is holding up. There is no indication in the data that workers are dropping out in vast numbers during the pandemic. But should that change, Jason’s work will be important to continue to track for Oregon.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.