By Josh Lehner,

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

As our office developed our latest forecast, we dug into Oregon’s slower employment growth. As discussed previously, we highlighted three main channels in which the slowdown could materialize: worsening current economic conditions, uncertainty over future growth, and tight labor markets. We tried to spell it out more clearly in our forecast document and during our forecast release. And while I believe all three channels are impacting the numbers and the outlook to a certain degree, Representative Reschke really pinned us down during testimony (in a good way, trying to get economists to stop doing the whole “on one hand … on the other hand” thing).

What I told Representative Reschke was that labor and the number of available workers was by far the largest factor behind Oregon’s slowdown. Uncertainty over future growth and a potential recession was the second largest factor, but at a tier below labor supply. And rising business costs and squeezed profit margins being the third largest factor, which was another tier below uncertainty.

Back to the issue of labor, there are a number of reasons I believe this is the largest factor. Economists’ views differ, but I’m not of the belief we are truly at full employment or beyond full employment. That said, there is no question Oregon’s labor market is stronger and tighter given the gains experienced in recent years.

Unemployment is at or near record lows. More importantly the share of prime working-age Oregonians with a job is back to where it was prior to the Great Recession, although not quite all the way back to the late 1990s. This means it is harder for firms to hire and expand even if they want to. I think we can see this in some of the data points discussed before: hiring is slower but layoffs are not higher. Given ongoing wage gains that are stronger than the nation, I think this points toward a tight labor market being a considerable factor in slower net job growth.

But beyond the general economic statistics, there are indications that Oregon’s labor supply is slowing more than expected at both ends of the pipe. These further my view on the impact of labor constraints, and if the numbers are to be believed, are more than enough to account for slower growth this year than what our office expected a year ago.

First, it is important to point out that the slowdown means Oregon is adding approximately 2,000 jobs per month so far in 2019. Underlying demographics suggest the state needs around 1,900 or so to hold the unemployment rate steady. Growth clearly remains solid.

As for the flows into the labor market, these appear to have slowed more than expected in 2019. Preliminary population estimates indicate that net migration was 11-12,000 below our office’s forecast. This would work out to approximately 6,000 fewer prime working-age Oregonians (25-54 years old) or 9,000 total fewer working-age Oregonians (18-64). Now, not all of these individuals would be looking for work, and we will get final 2019 estimates from Portland State here in another week or two so these figures may change some. That said, indications are migration was slower than expected, meaning the number of available workers for firms to hire is smaller than expected.

While annual population estimates are difficult, one year from now we will have the official 2020 Census population counts. This will provide a solid anchoring point for our office’s demographic research and forecast, and we will be able to better gauge migration flows in recent years. This doesn’t help our understanding today of course, but it is the demographic light at the end of the decade-long tunnel of data darkness.

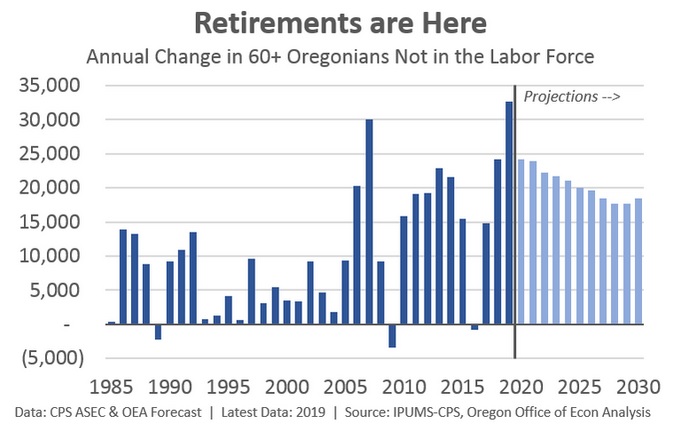

While the inflows into the labor market appear to have slowed, it also looks like the outflows into retirements are larger than expected this year. From our forecast:

Retirements appear to have spiked. The household survey indicates retirements are running some 7,000 or so higher than what would be expected based upon demographics and the aging population alone. To put the 7,000 increase in perspective, that is equivalent to three or four months of employment growth. This means even if firms hired replacements, the higher level of retirements could certainly impact net employment gains across the state.

All told, the sharper slowdown in migration and spike of retirements works out to something like a 15,000 labor supply drag in 2019. Given Oregon firms have added around 20,000 net new jobs so far this year (data through October), the labor supply drag is quite large. Now, about half of the drag — retirements — means firms hired more new workers than the net numbers indicate, while the other half — migration — means firms are trying to hire from a smaller pool of available workers.

As our office wrote two years ago: The labor market is tight and expected to remain so until the next recession. The cyclical issues will come and go, however the demographic crunch is finally upon us and here to stay for the foreseeable future.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.