Unsurprising evidence that hiking the minimum wage hurts low wage workers

On July 1, the minimum wage spiked in several cities and states across the country. Portland, Oregon’s minimum wage will rise by $1.50 to $11.25 an hour. Los Angeles will also hike its minimum wage by $1.50 to $12 an hour. Recent research shows that these hikes will make low wage workers poorer.

A study supported and funded in part by the Seattle city government, was released this week, along with an NBER paper evaluating Seattle’s minimum wage increase to $13 an hour. The papers find that the increase to $13 an hour had significant negative impacts on employment and led to lower incomes for minimum wage workers.

The study is the first study of a very high minimum wage for a city. During the study period, Seattle’s minimum wage increased from what had been the nation’s highest state minimum wage to an even higher level. It is also unique in its use of administrative data that has much more detail than is usually available to economics researchers.

Conclusions from the research focusing on Seattle’s increase to $13 an hour are clear: The policy harms those it was designed to help.

A loss of more than 5,000 jobs and a 9 percent reduction in hours worked by those who retained their jobs.

Low-wage workers lost an average of $125 per month. The minimum wage has always been a terrible way to reduce poverty. In 2015 and 2016, I presented analysis to the Oregon Legislature indicating that incomes would decline with a steep increase in the minimum wage. The Seattle study provides evidence backing up that forecast.

Minimum wage supporters point to research from the 1990s that made headlines with its claims that minimum wage increases had no impact on restaurant employment. The authors of the Seattle study were able to replicate the results of these papers by using their own data and imposing the same limitations that the earlier researchers had faced. The Seattle study shows that those earlier papers’ findings were likely driven by their approach and data limitations. This is a big deal, and a novel research approach that gives strength to the Seattle study’s results.

Some inside baseball.

The Seattle Minimum Wage Study was supported and funded in part by the Seattle city government. It’s rare that policy makers go through any effort to measure the effectiveness of their policies, so Seattle should get some points for transparency.

Or not so transparent: The mayor of Seattle commissioned another study, by an advocacy group at Berkeley whose previous work on the minimum wage is uniformly in favor of hiking the minimum wage (they testified before the Oregon Legislature to cheerlead the state’s minimum wage increase). It should come as no surprise that the Berkeley group released its report several days before the city’s “official” study came out.

You might think to yourself, “OK, that’s Seattle. Seattle is different.”

But, maybe Seattle is not that different. In fact, maybe the negative impacts of high minimum wages are universal, as seen in another study that came out this week, this time from Denmark.

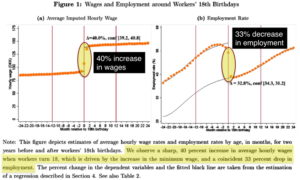

In Denmark the minimum wage jumps up by 40 percent when a worker turns 18. The Danish researchers found that this steep increase was associated with employment dropping by one-third, as seen in the chart below from the paper.

Let’s look at what’s going to happen in Oregon. The state’s employment department estimates that about 301,000 jobs will be affected by the rate increase. With employment of almost 1.8 million, that means one in six workers will be affected by the steep hikes going into effect on July 1. That’s a big piece of the work force. By way of comparison, in the past when the minimum wage would increase by five or ten cents a year, only about six percent of the workforce was affected.

This is going to disproportionately affect youth employment. As noted in my testimony to the legislature, unemployment for Oregonians age 16 to 19 is 8.5 percentage points higher than the national average. This was not always the case. In the early 1990s, Oregon’s youth had roughly the same rate of unemployment as the U.S. as a whole. Then, as Oregon’s minimum wage rose relative to the federal minimum wage, Oregon’s youth unemployment worsened. Just this week, Multnomah County made a desperate plea for businesses to hire more youth as summer interns.

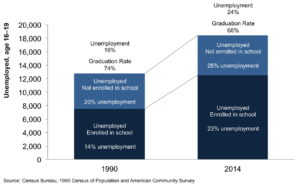

It has been suggested Oregon youth have traded education for work experience—in essence, they have opted to stay in high school or enroll in higher education instead of entering the workforce. The figure below shows, however, that youth unemployment has increased for both those enrolled in school and those who are not enrolled in school. The figure debunks the notion that education and employment are substitutes. In fact, the large number of students seeking work demonstrates many youth want employment while they further their education.

None of these results should be surprising. Minimum wage research is more than a hundred years old. Aside from the “mans bites dog” research from the 1990s, economists were broadly in agreement that higher minimum wages would be associated with reduced employment, especially among youth. The research published this week is groundbreaking in its data and methodology. At the same time, the results are unsurprising to anyone with any understanding of economics or experience running a business.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.