Key Workforce Challenges: Slow Job Growth

Key Workforce Challenges: Slow Job Growth

by Nick Beleiciks, Gail Krumenauer

Oregon Employment Department,

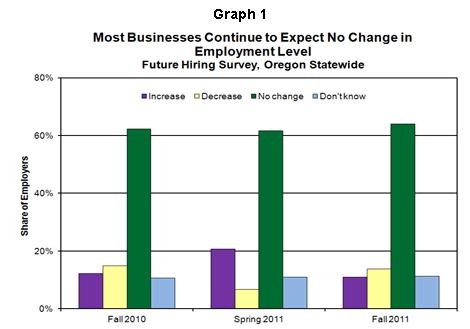

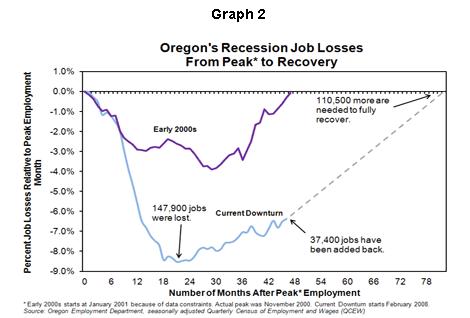

Job growth following the recession has been excruciatingly slow. One measure of employment, the number of jobs covered by unemployment insurance, shows that Oregon lost a net 147,900 jobs during the recession. During the next 25 months through December 2011, Oregon’s economy added back 37,400 jobs, just one-fourth the number of jobs lost during the recession. The slow pace of job growth has been one of the key workforce challenges facing Oregon.

Oregon’s Slow Growth Similar to the Nation

The recession sliced 147,900 unemployment insurance-covered jobs in the 21 months between February 2008 and November 2009. The losses represented 8.5 percent of covered jobs in Oregon. The rate of job loss was worse in Oregon than it was for the United States as a whole, which lost about 6.4 percent of jobs.

The rate of job recovery in Oregon has been similar to the nation. By the end of 2011, the job count had grown 2.4 percent from the lowest point, about the same as the nationwide growth of 2.3 percent through December. The U.S. job recovery has already taken longer to return to pre-recession employment levels than any other recession during the last 70 years, and there are still over 5 million jobs that need to be added to return to the pre-recession peak.

Construction, Financial Activities, and Government Stifling Job Growth

Job growth in construction and financial activities, two industries hit especially hard during the recession, has been conspicuously absent from private-sector growth during this recovery. The private sector added 44,000 jobs since hitting bottom in November 2009. However, construction added just 200 jobs and financial activities cut an additional 2,600 jobs. In fact, both construction and financial activities finally reached their respective low points of employment during 2011, long after the private sector had bottomed out.

Government also hit its employment low in 2011. Government operates on annual or biennial budgets at the state and local levels, and tends to experience a delayed response to economic downturns. While private employment plummeted by 151,300 jobs between February 2008 and November 2009, government added 2,500 jobs, boosted in part by funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). Local government education accounted for 1,700 of those jobs. Conversely, the recovery in private employment has been paired with a loss of 6,000 government jobs. Local education accounted for 4,300 of those post-recession government losses.

Most Employers Not Expecting to Expand Soon

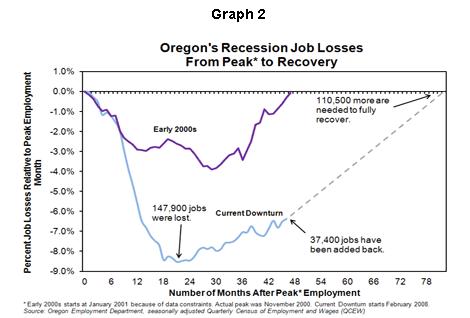

The Oregon Employment Department surveys employers to learn about their anticipated hiring. The latest results show that one-third of employers planned to hire between the fall of 2011 and May 2012. This didn’t reflect employment growth though. Most hiring was anticipated due to turnover or for seasonal work. One-tenth of employers indicated that their overall employment level would increase over the six-month period, while 14 percent expected employment levels to decline.

The fall 2011 survey showed similar results to previous findings (Graph 1). When the same survey was conducted in the fall of 2010, it showed that 36 percent of employers expected to hire, but that only 12 percent of employers anticipated an increase in employment levels. The spring of 2011 showed slightly more upbeat results, with 43 percent of employers indicating they would hire and 21 percent reporting that employment levels would rise. The message from employers over the course of the year has been consistent: more than 60 percent anticipate no change in the number of workers they employ.

Not surprisingly, the two industries with the smallest share of employers looking to hire in the fall of 2011 were financial activities and construction, two industries already dragging on job gains. The survey asked employers for reasons that may prevent them from hiring between the fall of 2011 and the spring of 2012. More than one-third (37%) of respondents cited the recession as a reason they may not hire, even two years after its technical end.

Most businesses continue to expect no change in employment level

At Least Two More Years Until Return to Peak

Oregon still needs to add 110,500 jobs to return to peak employment levels. That could take until the end of 2014, according to the current employment forecast from the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. Full recovery by then assumes average gains of more than 3,000 new jobs each month, a healthy pace and nearly double the rate of average job growth in 2010 and 2011.

Oregon’s job decline during the early 2000s lasted nearly four years from the start of job losses to full recovery. About 4 percent of jobs were lost at the worst part of that downturn, less than one-half the losses this time around. An initial recovery was held back by additional job losses in high-tech industries. But once growth took hold in 2004, monthly gains averaged a swift 3,800 new jobs per month (Graph 2).

It’s clear that the current downturn’s recovery has been slower than it was in the early 2000s and could take as long as 82 months (nearly 7 years) from the start of job losses to reach a full recovery. The dashed line in Graph 1 represents the timeline of the expected return to full job recovery based on current projections of total employment. However, the public sector, and some industries within the private sector, are expected to see even slower rates of growth.

Oregon’s construction industry jobs are expected to grow 2.5 percent in 2012, faster than the overall private sector’s growth of 1.6 percent, while financial activities is expected to grow by just 1.1 percent. Government is projected to decline an additional 1.2 percent in 2012.

Oregon’s recession job losses from peak to recovery

The Slow Growth Challenge Not Leaving Soon

Four years after the onset of the Great Recession, and more than two years after its end, the recovery continues to be characterized by slow job growth. A pick up in the pace of hiring is not expected anytime soon. Employers are still wary of the recovery and most do not plan to expand their number of workers. Employers are still hiring to fill vacancies left by staff leaving because of turnover, and they are hiring to fill seasonal positions, but surveys show that few businesses are planning to actually expand their number of workers.

Economic forecasters seem to agree that job growth in Oregon is expected to continue its slow upward climb. The current forecast predicts that employment will not return to the pre-recession peak until the end of 2014, making this tough job market a seven-year-long workforce challenge.

Slow job growth is one of eight challenges currently faced by Oregon’s workforce system. It is a particularly important one because it is a contributing factor to several of the others; its effects can be seen in the high number of unemployed, the number of individuals who have been unemployed for a long time, and the number of young people facing particularly difficult times as they seek to enter the workforce.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.