The Great Recession Didn’t Make Health Care Bleed

The Great Recession Didn’t Make Health Care Bleed

By Jessica Nelson

Oregon Employment Department

Looking for silver linings in the economy after the Great Recession, the health care industry often surfaces. Well before the Great Recession, many analysts saw health care as “recession proof,” a simplistic label the industry made a valiant attempt to live up to again in recent years. The argument is logical; after all, none of the drivers of health care industry growth go away during a recession. The population still ages, people still get sick and injured, and babies continue to be born.

The “recession proof” label is misleading, however, because when industries are so closely tied in financing, supply relationships, and reliance on the mood of investors, no industry can hope to escape unscathed from a downturn like the Great Recession. Health care growth may not have stopped or reversed course, but it did slow the past few years. And the effects of the Great Recession linger, especially in government budgets, which will affect health care growth, possibly for years to come. We could quibble all day about whether the industry deserves that lofty label, but instead let’s examine the industry itself.

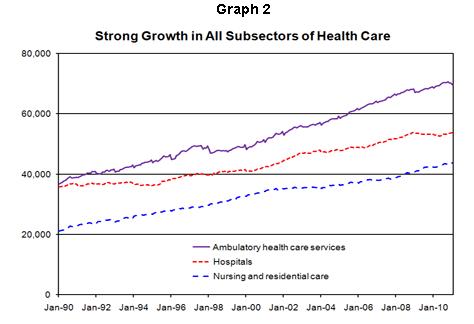

Health care employment growth has outpaced total job growth for years. From 2000 to 2007, the Oregon health care industry added jobs at an average pace of 3.0 percent per year. During the same period the total nonfarm employment growth rate averaged 1.1 percent annually. This divergence in growth rates took place after a decade when health care matched the growth rate of total nonfarm employment – each had an average annual growth rate of 2.6 percent during the 1990s. Oregon total nonfarm employment peaked in November 2007, and dropped 11.0 percent by the trough in January 2010. Over the same 26-month period, health care grew by 4.7 percent. Graph 1 is reminiscent of a dagger in the heart of Oregon’s economy – that steel blade striking deep into employment levels lasted 26 months. Health care didn’t bleed jobs over the year for a single month during the Great Recession.

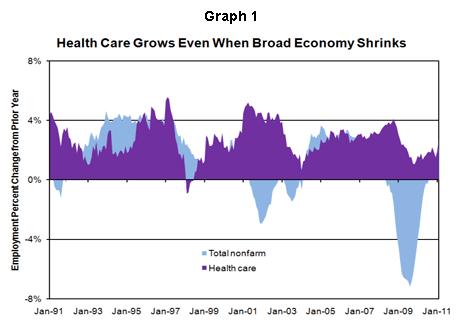

This is possibly the most boring graph ever published by the Oregon Employment Department – employment trends since 1990 in each subsector of the health care industry (Graph 2). There are three subsectors that make up health care:

- Ambulatory health care services include doctors’ and dentists’ offices as well as establishments of other practitioners, usually not providing inpatient services.

- Hospitals include private establishments providing inpatient services, and outpatient services as a secondary activity, many of these services can only be provided using specialized facilities and equipment.

- Nursing and residential care facilities provide residential care combined with nursing, supervisory, or other forms of care required by residents.

Since 1990, each subsector of health care steadily expanded in terms of job counts. Nursing and residential care grew the most, more than doubling since 1990. Ambulatory health care services nearly doubled, growing 92 percent. Hospitals had the lowest rate of growth over the period, at 50 percent, but that still outperformed total nonfarm employment’s growth of 32 percent since 1990.

The distribution of health care jobs across the three subsectors also changed since 1990 (Table 1). Ambulatory health care services increased their share of the health care pie, as have nursing and residential care facilities. Hospitals account for a smaller share of today’s health care jobs than they did two decades ago.

Just how many jobs are we talking about? In total, health care employs close to 170,000 Oregon workers. More than 70,000 work in ambulatory health care services, another 54,000 staff the states’ privately owned hospitals, and 44,000 work at nursing and residential care facilities.

Health care now makes up more than one-tenth of Oregon employment, up from about 8 percent during the 1990s. Nationally, the same pattern has taken hold, with health care’s piece of the employment pie creeping above 10 percent in 2009 and 2010, as other sectors hemorrhaged jobs. With an aging population, it makes sense that health care is a bigger part of the economy. However, it also makes sense that as other areas of the economy expand after severe job losses during the recession, health care’s slice of employment will return to a historical norm, probably below that 10 percent mark.

| Dynamic Industry Mix Within Health Care | |||

| Ambulatory Health Care Services | Hospitals | Nursing and Residential Care | |

| 1990 | 39.5% | 37.7% | 22.8% |

| 2010 | 42.1% | 32.0% | 25.9% |

Two of the subsectors of health care pay wages above the average for all industries. In 2009, Oregon’s average pay per worker amounted to $40,742. Ambulatory health care services paid an average of $56,488. Hospitals averaged $53,711. Nursing and residential care, on the other hand, paid much less than the state average, at $23,135.

Simple averages don’t tell the whole story in such a broad industry. While many health care occupations pay high wages, many are also low-wage jobs. To complicate matters, as the industry adds jobs we don’t know precisely which occupations are currently growing. The 20 largest health care occupations in Oregon are listed in Table 2, with their 2010 annual mean wage, and the variety of positions and wages is striking. (Please note: the employment data in the table is health care industry specific, but the mean wages listed are for the occupation across the economy.) The industry’s largest occupation is a high paying one: registered nurses employed in health care numbered more than 24,000 in 2008 and Oregon’s registered nurses made almost $74,000 on average in 2010. The next two occupations (nursing aides and home health aides) show the flip side of the coin – lots of health care personnel don’t make high wages.

Also, not all health care jobs are in health care specific occupations. The state’s hospitals, doctors’ offices, and nursing homes need receptionists and office clerks, billing clerks, and maids and housekeeping cleaners – all of these occupations made it into health care’s top 20 shown in Table 2.

| Oregon’s Largest Health Care Occupations | ||

| 2008 Health Care Employment | 2010 Annual Mean Wage | |

| Registered Nurses | 24,046 | $73,961 |

| Nursing Aides, Orderlies, and Attendants | 11,413 | $27,131 |

| Home Health Aides | 7,583 | $21,988 |

| Medical Secretaries | 7,497 | $33,153 |

| Medical Assistants | 6,420 | $32,469 |

| Physicians and Surgeons | 6,057 | N/A |

| Personal and Home Care Aides | 4,370 | $22,657 |

| Dental Assistants | 4,162 | $37,895 |

| Receptionists and Information Clerks | 4,051 | $26,429 |

| Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners | 3,206 | $21,360 |

| Dental Hygienists | 3,103 | $78,214 |

| Office Clerks, General | 2,791 | $29,745 |

| Healthcare Support Workers, All Other | 2,447 | $33,389 |

| Billing and Posting Clerks | 2,233 | $33,884 |

| Licensed Practical and Licensed Vocational Nurses | 2,120 | $45,228 |

| Medical and Health Services Managers | 2,095 | $97,389 |

| Medical Records and Health Information Technicians | 2,084 | $35,275 |

| Radiologic, CAT, and MRI Technologists and Technicians | 2,007 | $60,536 |

| Interviewers, Except Eligibility and Loan | 1,934 | $31,431 |

| Social and Human Service Assistants | 1,924 | $28,617 |

Health care is expected to be one of the fastest growing industries both statewide and nationally between 2008 and 2018. The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics gives some reasons for anticipated growth in its Career Guide to Industries. Among the contributing factors, BLS lists: fast growing population in older age groups; a higher incidence of injury and illness among older age groups; improved survival rate of severely ill and injured patients who need extensive therapy and care; early diagnoses increasing ability to treat conditions; and increased demand for dental care as people retain their natural teeth longer.

If any industry deserves the label “recession proof,” it is health care. The sector tenaciously held its pattern of job growth, albeit at a slower rate, throughout the Great Recession. However, lingering effects of the recession continue to play out, and strapped government budgets may mean slower growth for health care for some time. Only time will tell, but after the past few years, thanks to health care for giving this economist something positive to say.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.