Trade War: What Does It Mean for Business and the Economy?

Trade War: What Does It Mean for Business and the Economy?

By Bill Conerly,

Conerly Consulting, Businomics

“Trade wars” proclaimed recent headlines. Here’s a guide for what business leaders should know about the controversy. There are two battle tactics to understand: exchange rate devaluation, and tariff/quota policy.

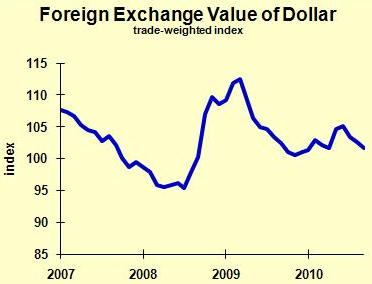

The U.S. dollar exchange rate has been falling, while other countries also want their own currencies to fall. However, it’s clearly impossible for every country’s exchange rate to fall. When one exchange rate falls, the trade partner’s exchange rate rises. The easiest way to understand the dollar’s exchange rates with many different countries is to average them, using weights based on how much trade we do with each country.

Why would a country want its exchange rate to fall? A falling exchange rate stimulates the economy. First, exports are more affordable to foreigners when the dollar is cheap. Second, our own consumers and businesses find buying American products more affordable than imports when the dollar is cheap. There’s no doubt that the falling dollar by itself is stimulative, however there have been times when the factors that trigger a fall in an exchange rate are disastrous for the economy. But for the United States right now, a falling dollar is good for the economy.

However, the common view that governments can manage their exchange rates is misleading. If the Treasury starts selling dollars and buying Euros or Yuan, that would seem to push down our exchange rate. However, if the dollars simply come from our own economy, the private sector players will trade until they get their dollar holdings back where they want them. This “sterilized” intervention in foreign exchange markets has no lasting effect.

However, if the Federal Reserve prints up new dollars to be sold to foreigners, then the exchange rate declines. Yet, if the Fed prints up new dollars and distributes them to Americans, the dollar exchange rate also declines. It turns out that the only effective way to push foreign exchange rates around is to increase or decrease the country’s money supply.

What’s happening in today’s trade wars is countries want lower exchange rates, and if they will print up enough of their currency, they can get them.

What happens if all countries print more money? Initially the world economy booms. Then it hits limits to productive capacity, at which point all the global currency becomes inflationary. (That’s a bit of a simplification, but the gist of the story is accurate.)

Given the weak state of the advanced economies, it makes sense for them to increase their money supplies, pushing down their exchange rates. The major country this does NOT apply to is China, which has very strong growth. It makes sense for them to tighten up monetary policy, allowing their exchange rate to rise–just as the Obama Administration is jawboning them to do.

The Chinese should pursue a rising Yuan policy because it’s good for them. It’s also good for us, but that doesn’t sell very well back in Beijing. Chinese policy has subsidized their own manufacturers and AMERICAN consumers, at the expense of U.S. manufacturers and Chinese consumers. Now it is time for them to reverse that policy.

The second battle tactic in a trade war is raising tariffs and quotas on imports. This is “beggar thy neighbor” policy, which aims to make the other guy worse off. If everyone does it, the whole world economy shrinks. It may sound good to “protect American jobs,” and it may help some readily identifiable workers, such as steel workers. The cost, however, is to force Americans to pay more for the goods they buy, both imported goods as well as domestic goods that compete with imports, or even domestic goods that use in the production process imported goods. This kind of trade war is disastrous for the whole world. Google “Smoot Hawley tariff” to learn more.

Business Planning Implications: Businesses that are heavily involved in international trade should pay attention to this issue. That includes companies that buy or sell from other companies involved in international trade. (Example: you are a manufacturer; you buy components from other U.S. countries, but your suppliers buy from foreigners.)

Expect the United States to push our foreign exchange rate down versus the Yuan and the exchange rates of relatively strong economies. However, Europe and Japan may be in the same boat as us, and it’s hard to say which countries will push harder for exchange rate devaluation. It could go either way. Time for some contingency planning for a fast-moving exchange rate.

On the tariff/quotas issue, stay tuned to Washington policy. This is, as much as I hate to say it, a time to keep paying your lobbyists. The worst outcomes often befall the companies who are not at the table when stupid foreign trade policies are adopted.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.