It’s the longest recession in the modern era for both the U.S. and Oregon. After a major decline in 2008 and 2009, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) resumed growth in the last two quarters of 2009. GDP is the measure of the value of all goods and services produced in the U.S. Conventional wisdom holds that two quarters of GDP growth indicates the end of the recession. While the National Bureau of Economic Research has yet to proclaim the recession officially over, major sectors of the economy seem to be stabilizing after two years of decline.

It’s tempting to proclaim the recession over. But economic recovery is a complex process. Some industries grow faster while other industries may fail to recover at all. The recovery may be strong and sustained or weak and short lived. As certain industries grow, or fail to grow, we’ll see indicators about the shape of the new Oregon economy born out of the worst recession in more than a generation.

Staffing companies, once a niche service, became a vital part of the U.S. economy in the 1990s. Today, 2 percent to 3 percent of U.S. workers are employed by a staffing company. Watching this industry provides important clues as to future movements in the economy as a whole.

During a recession, hard hit businesses cut expenses to stay profitable. For the vast majority of firms the largest expense is the payroll of its employees. Once orders begin to pick up, firms often turn to staffing companies to provide temporary workers – before hiring permanent employees. Conversely, when times are tough, temporary workers are often the first to be let go. Labor economists consider employment through these firms to be an important leading indicator of future economic conditions.

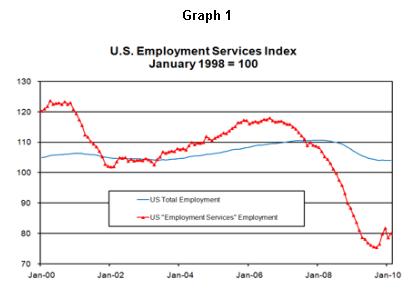

At the start of the 2001 recession, jobs began to decline in the U.S. in February 2001 (Graph 1). During the subsequent, and unusually long “jobless recovery,” jobs continued to disappear for the next two and a half years. The employment services industry that includes staffing companies was particularly hard hit during the recession. More interestingly, the industry began to decline a full 10 months before economy-wide job losses began. During this most recent recession, employment services began declining in August 2006, more than a year before the entire economy began losing jobs at the end of 2007. This suggests that the industry is an excellent predictor of a coming recession.

If job loss in the employment services industry can signal a coming recession, might job gains in the sector be a premonition of economy wide job growth? The data implies that it can. Employment services began growing in the U.S. in the spring of 2003, four months before the national job recovery took hold. The Oregon data is very similar, with the industry growing in early 2003, followed by statewide job numbers in the summer.

The most recent data is hard to read. Nationally, employment services has been generally trending upward since bottoming out in September of 2009. In Oregon, the picture is less clear. There’s a large amount of seasonality in this field, with jobs growing every summer and declining every winter. Adjusting for this seasonality, employment has been fairly flat since April 2009, and losing a little less than 5 percent of all jobs in the past 12 months. For most industries a 5 percent annual decline would be rough, but this industry is unique – it lost 20 percent in 2008. Looking at recent trends, it’s easy to imagine the industry entering a growth mode in the middle of 2010.

A note of caution about this leading indicator should be considered. In the first half of 2002, in both Oregon and the U.S., this industry showed modest growth before retreating again in the last half of the year. After the false signal in early 2002, total U.S. industry job counts were essentially flat for at least another year.

Once economic recovery starts, what drives economic growth? In a word, construction. Coming out of recessions, the U.S. economy has traditionally relied on an expanding housing market to provide the greatest boost to the economy as a whole. Oregon – with our timber, saw mills, wood product manufacturing firms, and international ports – has long benefited disproportionately from strong home construction.

In order to stimulate economic growth during recessions, the U.S. Federal Reserve takes steps to lower the interest rate. A low interest rate makes it more attractive for businesses and individuals to borrow money. Lowering interest rates encourages businesses to take risks on expansions, open new locations, expand product lines, and hire new workers.

The effect of low interest rates is probably most visible on the residential housing market. In early 2000, the average 30-year fixed mortgage in the U.S. was almost 8.5 percent. By the middle of 2003, due to policy actions taken by the U.S. Federal Reserve, those rates had dropped to about 5.5 percent. This decline of about 3 percentage points had a significant effect. As interest rates fell, millions of homeowners refinanced their mortgages, saving thousands of dollars each year in mortgage payments. Millions more Americans either bought their first, now affordable, home or upgraded to a larger or new home.

Millions of new mortgages funded a housing boom. As during most economic recoveries, low interest rates fed the entire housing industry. Construction firms, wood product manufacturers, hardware stores, realtors, and mortgage firms all hired tens of thousands of employees in Oregon to keep up with demand. From 2003 to 2007, construction grew by almost 30,000 jobs in Oregon, representing 35 percent growth in four short years. Construction became the most visible success story in the federal government’s efforts to create family wage jobs.

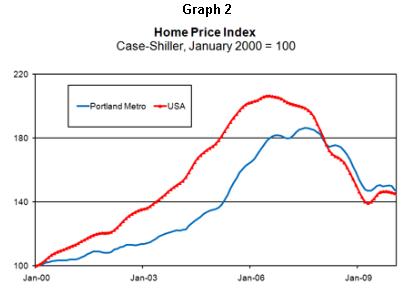

The value of homes skyrocketed as well. According to the Case-Shiller index, U.S. home prices more than doubled from 2000 to 2006 (Graph 2)! During this time, the Portland Metro area saw home prices grow by about 80 percent. Nationally, the most visible sign of post-2001 recession prosperity could be seen in the housing markets. President Bush boasted in his 2004 State of the Union address that home ownership rates were at record high levels. A rare bright spot in an otherwise jobless economic recovery.

Will an expanding housing market once again propel the Oregon – and U.S. – economy? In the near future, that seems doubtful. Home prices, certainly overvalued, began to collapse in 2006. In the last few years, the average U.S. home has lost more than 25 percent of its value. The decline in the Portland metro area is only slightly less severe. Almost one in four U.S. homeowners are underwater on their mortgage. That is, they owe more money on their mortgage than they would likely get by selling their home. Banks and mortgage brokers are now much more careful about lending money to aspiring home owners. Meanwhile, entire condo developments, built during the housing boom, have sat empty and unsold for years in the Portland area.

In every recent economic recovery, an expanding housing market played a critical role in creating jobs and spreading prosperity. With the collapse of the housing market, the economy is now burdened with unsold homes, essentially bankrupt homeowners, and armies of unemployed construction workers. It seems unlikely that a broad economic recovery would be possible without a robust housing sector. Increasing home values that would lead developers to once again buy raw materials, hire workers, and build houses, would seem to be not just a signal of broad economic growth, but a necessary condition for growth to occur.

Economic growth and job creation are great, but what about the economic indicator that people care the most about – the unemployment rate?

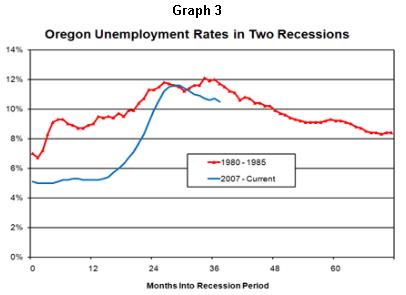

During the summer of 2009, the Oregon unemployment rate reached 11.6 percent, close to the record high from late 1982. Over the last several months, the unemployment rate declined by about one full point. Ironically, as the unemployment rate dropped, jobs continued to disappear as well, declining by more than 1 percent over the same time period.

How can the unemployment rate drop as businesses continue to shed jobs? It’s important to remember that the unemployment rate is more than just a simple indicator, it’s a ratio involving the number of people seeking jobs as a part of the total labor force. Populations grow and decline, workers become discouraged and full time workers shift to part time work or self employment. The labor market is a complicated and dynamic system. The unemployment rate can only provide a snapshot summary of this complexity.

Most economic forecasters expect the U.S. and Oregon economy to begin creating jobs, month after month, at some point in 2010. But this may not move the unemployment rate significantly. Over time, the U.S. workforce grows, both from immigration and students leaving school and entering the workforce. The U.S. economy needs to grow by about 100,000 to 150,000 jobs every month just to keep up with population growth.

It’s easy to imagine Oregon job growth at a rate that fails to out pace population growth. In that case, the unemployment rate would not significantly decline until job growth reaches at least 2 percent a year. The most recent economic forecast by the Oregon Department of Administrative Services does not expect Oregon to begin growing that fast until early 2011. The same forecast sees growth peaking in 2012 and slowing to only a little more than 2.2 percent in 2013.

It’s difficult to reliably forecast future unemployment rates, but history suggests it will take much longer for the rate to drop than it took for the rate to surge during the recession. During the recession of the early 1980s, the Oregon unemployment rate shot up 5 percentage points to 12 percent in three years (Graph 3). As dramatic as that increase was, 2007 was even worse, with unemployment surging by more than 6 percentage points in the two years ending in the summer of 2009. Three years after the unemployment rate peaked in late 1982, the Oregon unemployment rate had only declined to a still painful 8.5 percent. Should that pattern hold again this time, Oregon could see unemployment rates higher than 8 percent well into 2013.

Disclaimer: Articles featured on Oregon Report are the creation, responsibility and opinion of the authoring individual or organization which is featured at the top of every article.