By Josh Lehner

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

Included in the American Rescue Plan Act were some significant changes to the child tax credit for 2021. While some policymakers are looking to make these changes permanent, at this point they are for just 2021 only. These changes include an increase in eligibility, an increase in the size of the credit, and switching from a one-time credit every year when filing tax returns to periodic (monthly) payments directly to families. Each of these changes is noteworthy by itself and what follows takes a look at the implications here in Oregon.

First, the financial benefit for Oregon families is significant. The previous credit was for $2,000 per child less than 17 years old. The new credit is for children under 18 years old. For kids under 6 the amount is increased to $3,600 while those 6-17 years old it is increased to $3,000. Importantly the credit is also now fully refundable, allowing lower income families to receive the full amount unlike in years past.

Roughly, these changes increase Oregonian after-tax income by $1 billion or so. Building an analysis off of Census data, like our office does here, gets us $1 billion while sharing down the federal budget cost gets us more like $1.3 billion in Oregon.

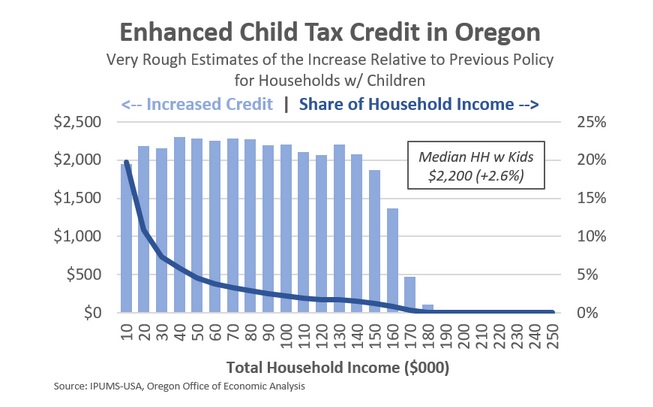

Overall about 85% of Oregon families — defined as a related child and adult — will receive the enhanced credit due to the income limits of $75,000 filing single, $150,000 married filing jointly. For most families, the increase is right around $2,000 relative to the old credit. Broadly speaking the easiest way to think about this is the credit increased from $2,000 to $3,000 for most kids and the average family has two kids. There’s more nuance here based on expanded eligibility and the age of the kids but overall it mostly seems to even out to around $2,000 for most eligible households.

The enhanced child tax credit is a progressive policy, as seen in the chart below. Yes, it is a fairly flat, evenly distributed $2,000 for most families, however the boost in after-tax income this provides is much larger for lower-income households. For example, the median household with kids earns around $85,000 per year. They will receive a 2.6% boost in income from the enhanced child tax credit. However for households in poverty the boost is more like 5, 10, 15% or more. Researchers at Columbia University estimate that the enhanced credit will reduce U.S. child poverty by 45%, and by 46% here in Oregon. (Note that the chart below does not factor in the increased refundability.)

Additionally the enhanced credit will lessen racial and ethnic income disparities as well. This is for at least two reasons. Yes, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Oregon generally earn less money than their white, not Hispanic peers. However younger generations are also more diverse than older cohorts in the state. So young families are more likely to be diverse, and also earn less money because one parent may stay home to look after the kids and even those that are working are more likely to earn less income because s/he is still relatively early in her/his career.

Specifically what this analysis shows is that households with white, not Hispanic kids account for 66% of aggregate family income. However such households account for 59% of the increase in the credit. Put another way, households with BIPOC children account for 34% of income but will receive 41% of the increased credit. These relative changes are not drastically different, but boosting family-friendly policies do work to lessen racial and ethnic disparities.

Second, while the overall boost to after-tax income is great for families, the switch to periodic payments has big implications as well. The IRS just announced they are expecting to begin monthly payments in July. Families will get half of the credit on their tax return when they file in April 2022, but the other half will be in direct payments from July through December 2021. As such, starting this summer, parents will begin receiving $250 or $300 per month per child, depending upon the child’s age.

As the Sightline Institute summarized last year, cash benefits offer flexibility for recipients that allows them to better spend on the things they need instead of being tied to specific products or categories. Additionally, monthly payments also better allow households to build the money into their regular budget and plan better financially then relying upon a large, one-time payment that is intertwined with everything else on a tax return. (Note this was part of the rationale with Make Work Pay, the Obama era payroll tax cut designed to boost household incomes coming out of the financial crisis.)

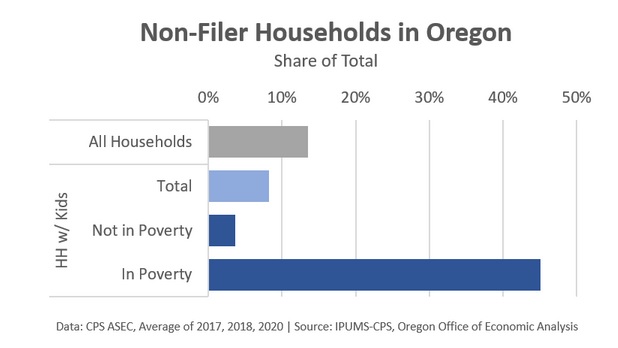

Third, the enhanced credit is being administered by the IRS. The IRS has a lot of recent experience dispersing the recovery rebates during the pandemic, which works quite well for the majority of households. However, that means it works well for those who file tax returns. If your family is a non-filer, usually because your income is below the filing threshold, signing up to receive the enhanced credit and monthly payments creates administrative hurdles. As the People’s Policy Project points out (H/T Michael Andersen), BIPOC families and those in poverty are much more likely to be non-filers. It’s based on a very small sample size here in Oregon, but we do get a question once a year about tax filing status from the household survey. As seen in the chart below, families in poverty are much less likely to file taxes, which means receiving the enhanced benefits requires more outreach and paperwork. This is something to keep an eye on in terms of policy effectiveness. The enhanced credit can only reduce poverty and boost family incomes to the extent that those eligible actually receive it.

Fourth and finally there may be some broader societal responses should such a policy be made permanent. We know childhood poverty impacts outcomes as an adult. For example, growing up in concentrated poverty is particularly bad for economic mobility. Should we see greater economic mobility in the decades ahead, that would be great news overall.

That said, recent discussions about unintended consequences tend to focus more on how parents will respond should they receive larger government benefits. Specifically will labor supply decline, leaving comparatively fewer available workers?

In short the answer is maybe. Some past research found that married spouses do work less when benefits increase. This is presumably an indication that one spouse was the primary earner and the other one worked to augment their incomes. The need to work a few hours on the side is lessened when benefits increase.

However, brand new research finds that the reforms and enhancements that Canada did a few years ago has not led to reduced labor supply, at least among single moms. Overall the Canadian reforms look a lot like the current 2021 child tax credit in the U.S., primarily a $3,000 child allowance that is paid out monthly. The linked paper above finds that the reforms did lead to a reduction in child poverty, an increase in after-tax income for parents, and no impact on labor supply. The focus on labor was primarily comparing employment among single moms and single women without kids. As such, it does not rule out any married spouse responses, but overall the findings are quite strong in terms of the policy outcomes.

Bottom Line: The enhanced child tax credit for 2021 will provide a noticeable boost to family incomes in Oregon and across the country. Based on the available data, and a similar Canadian policy, childhood poverty is set to decline in 2021. It is important to keep in mind that public policies can create unintended consequences. At some point there is a tradeoff between the generosity of government programs and earned income. But we also know that forcing children into poverty so that their parents have to work isn’t a great baseline either. A key question is where do we draw that line? Better yet how do we design programs to avoid fiscal cliffs, and high marginal tax rates as households move up in the income distribution? Monitoring the socio-economic outcomes from policy changes, and then adjusting those policies as needed is paramount. However to really analyze such changes, the enhanced child tax credit, or something of its ilk, needs to last more than a single year.