By Josh Lehner

Oregon Office of Economic Analysis

Economic growth over the long run is determined by the number of workers and how productive they are. The main reason Oregon outperforms the typical state over the entire business cycle is our stronger population growth. In particular, the influx of young, skilled households boosts our economic potential as our working-age population increases faster than in much of the country.

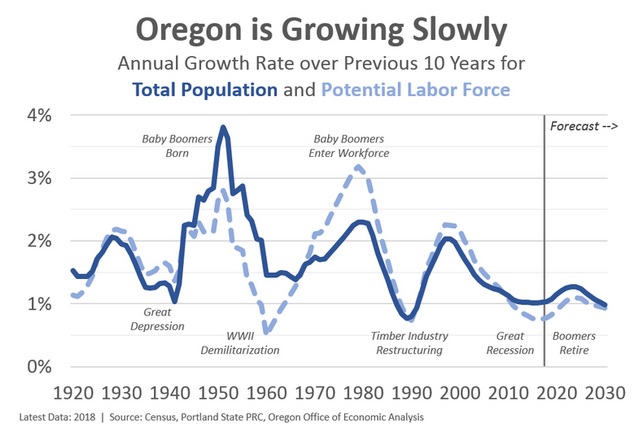

The big economic problem today is that demographics have turned into a major headwind. First, overall population growth is as slow as we have experienced in the past hundred years. It is not expected to pick up significantly either. Second, Baby Boomer retirements mean the working-age population is growing even slower and in many places around the country it is shrinking.

Our office’s measure of the potential labor force — taking demographics and adjusting based on participation rates by age — is expected to increase in the 2020s at half the rate Oregon experienced in the 1990s and one-third the rate as back in the 1970s when the Boomers entered into the workforce. Our economy will continue to grow and outstrip the typical state. However this growth will be significantly slower than we have become accustomed to. This has been the underlying character of our office’s forecasts for years as these trends directly translate into fewer job gains and slower growth in business sales and tax revenues.

Furthermore, these demographic headwinds have profound effects on nearly every economic measure we have, as is laid out in a great, new report [6] from the Economic Innovation Group. (See Neil Irwin’s NYT article [7] of Richard Florida’s post [8] for good summaries.) The following quote from the report highlights the key points and issues:

The demographic decline facing large parts of the country are not benign. Demographic decline and population loss are not just symptoms of place-based economic decline, they are direct causes of it… Population loss reverberates through housing markets and municipal finances. Low-growth places have weaker labor markets and suffer from less economic dynamism.

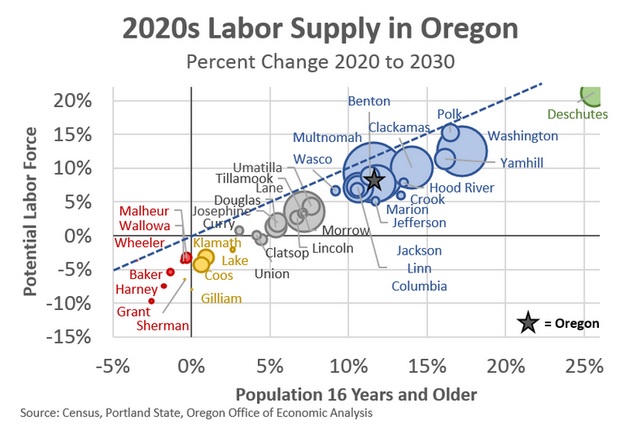

Much of the report focuses on not just the demographic challenges, but how they vary across the nation. As the authors note, roughly half of U.S. counties lost population over the past decade and 80% lost prime working-age population (25-54 years old). Here in Oregon it is not quite as dire as “only” 3 of our 36 counties saw minor population losses during the past 10 years (Grant, Harney, Sherman). Relative to the rest of the country, these counties fall more in the middle of the distribution given the worse trends in the Northeast and Midwest. Oregon demographics as a whole are better off than much of the country. We are seeing stronger population gains and more widespread gains across the state. That said, Oregon is not immune and face the same big picture issues, albeit to a slightly less degree.

In terms of the outlook, demographics are going to get worse before they get better. Over the coming decade, according to the latest Portland State forecasts, Oregon’s counties will avoid significant population losses, although there will be some. That’s the good news. However 11 of our 36 counties will experience a shrinking potential labor force. In 2030, there will be fewer residents available for work and likely fewer workers overall in these counties. A few other counties will see no growth in their potential labor force. Overall, the number of residents available for work in every single county will increase at a slower rate than total population growth due to underlying demographics.

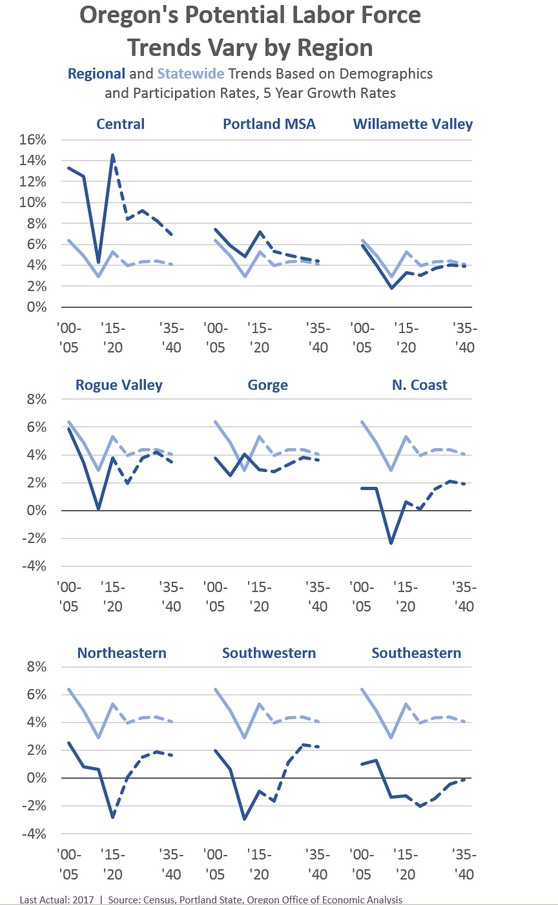

However, the outlook does not call for a downward spiral forever. Once we get past the bulge of upcoming retirements, the outlook improves. In particular, rural Oregon will see the biggest swings and improvements relative to recent years. This is something our office tried to highlight [10] a few years ago.

When it comes to the demographic drag, what matters is aging from one’s 50s to one’s 70s. This is when people go from their peak-working and peak-earning years to nearly everyone being retired. Given demographic trends, including some young adults moving away to urban areas, rural communities are nearly all the way through the demographic drag. You can see this below where the growth rates all pick up considerably for the North Coast, Northeastern, and Southwestern Oregon. Even Southeastern Oregon, which faces the biggest demographic and population growth challenges, goes from losses to relative stability.

Conversely, while urban Oregon will still outpace rural areas, the state’s fastest-growing areas are set to slow down in the coming years. The inflow of new migrants will be slower as migration rates trend down and the demographic drag hits; the Gen Xers and Millennials who moved to Oregon in recent decades will get to retire someday, probably. As such, growth will taper in Central Oregon (Bend mostly) and the Portland region. Oregon’s other urban areas like the Rogue and Willamette Valleys will see relatively steady gains.

Demographics are a very powerful force. For now they are largely pointing in the wrong direction. The EIG report notes that by 2037 two-thirds of U.S. counties will have fewer prime working-age adults than they did in 1997. Here in Oregon we are not immune but are somewhat better off given migration flows. From 2000 to 2040, 14 Oregon counties will have a smaller prime working-age population and 11 of them will have a smaller potential labor force.

A slower-growing and in some places an outright smaller economy is and will be a tremendous challenge. It weighs on the workforce, housing markets, business sales, and public services. That said, if the latest population forecasts are reasonably accurate, the trends will be improving in a handful of years as we reach peak retirements.

Finally, the report dives into a lot more information (do read it) but one item it discusses in educational attainment. Our office looked at this in our Rural Oregon report [12] as well. Now, one potentially complicating factor is the lack of an urban wage premium today for those without a college degree. It is possible that this will further alter migration and demographic patterns but it is still too early to tell if and how much.